An interview with Marc Van Montagu

In honor of his 90th birthday and impressive career

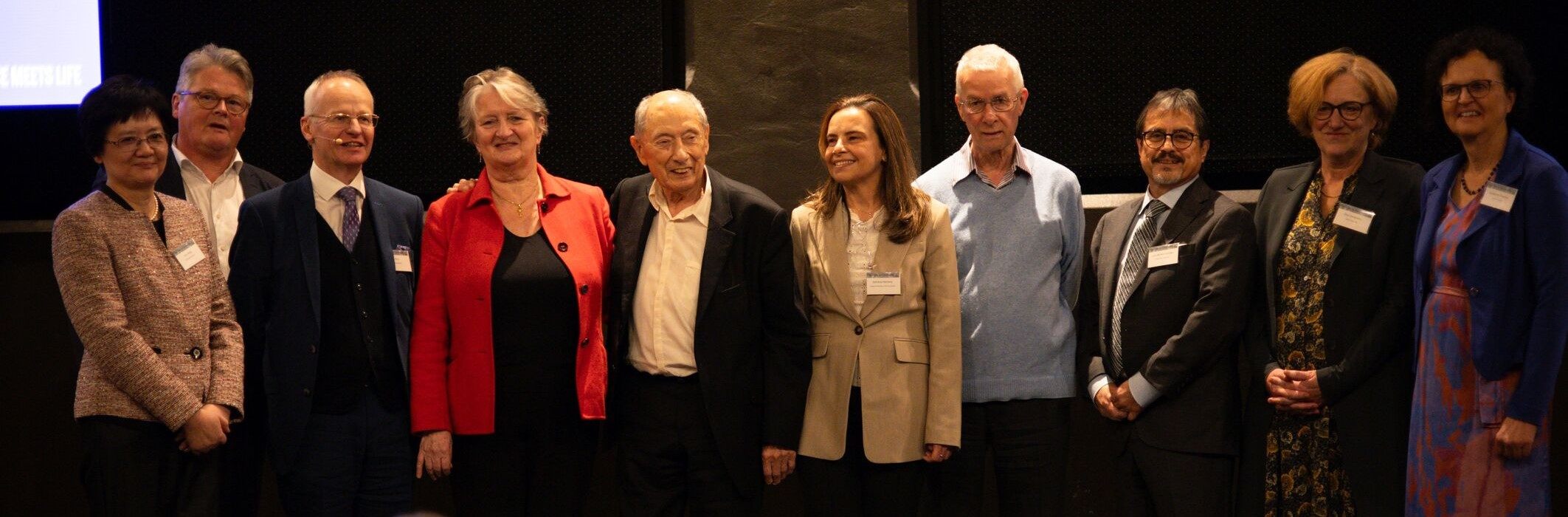

Professor Emeritus Marc Van Montagu turned 90 this month. On the occasion of this festive news and in honor of his spectacular career, we arranged an interview with him. Marc Van Montagu was the founder of the transformation technology with Agrobacterium tumefaciens, he was the director of the Department of Genetics at VIB-UGent, and he founded the companies Plant Genetic System (PSG) and Cropdesign, along with Johan Cardoen and Dirk Inzé. He has received several prestigious awards, nine honorary doctorates, and is a member of eleven academies. He has published more than 1100 articles and has been cited over 90,000 times. Sufficient reasons, therefore, to be granted the title of "Baron" by the Belgian royal family in 1990.

Congratulations, Mr. Van Montagu, on your 90th birthday and, of course, on your impressive career. If I may go back in time for a moment, how did you get involved in science? Did you always have an interest in science?

Certainly! As a child, I was already fascinated by sciences. I remember well that in 1947, my high school introduced the Latin-Sciences program. It was a new program with passionate teachers and an original curriculum. Organic chemistry was part of the curriculum. Before that, mainly inorganic chemistry was taught in Belgium. I can't explain why, but the chemistry of living beings attracted me immensely. It was a kind of intuition that drew me to this study. It was my introduction to biochemistry, and I was immediately hooked. I read a lot of science books in my free time and even built my own lab in the attic. This was long before the time of central heating, and the attic was not heated. So, I could only do my experiments there in the summer (laughs).

In addition, I was fortunate to meet Lucien Massart at high school, a professor of biochemistry at UGent. He advised me to study pharmacy because of my love for chemistry and biology. But in my mind, that meant standing in a shop all day. So, I stubbornly chose chemistry and also took courses in biology - such as descriptive plant biology. In my last year of chemistry, I did my licentiate thesis with Lucien Massart in ‘54-‘55, becoming the first student to do so. From here, my scientific career really took off.

It may be difficult to choose a moment in such a rich career, but what are you most satisfied with in your career?

I can't answer that. I am mainly satisfied with the whole process, not one or more isolated aspects. The knowledge we acquire is an exponentially rising curve, and I am very happy to have contributed to that curve. At the same time, our ignorance is also an exponentially rising curve. The more we know, the more new questions arise. That keeps me grounded.

.png)

Is there a work (a publication, book, etc.) or a person who inspired you in your career or daily life?

I am always impressed by people who can make decisions and implement ideas concretely. It is also these kinds of people who have helped me take certain steps. In English, they call this "nudging," and there are quite a few people who have "nudged" me.

First and foremost, my wife. We have been married for almost 67 years now, although everyone predicted that we would separate after 6 months (laughs). She really pushed me forward.

I also want to mention Laurent Vandendriessche. He was a professor at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at UGent and would later become the first rector of UIA Antwerp. I started with him as an assistant in 1955, along with Walter Fiers. Vandendriessche emphasized the importance of looking beyond national borders. The United States and the UK were then the epicenter of biochemistry and genetics.

Finally, there is also the book "Thinking, Fast and Slow" by Daniel Kahneman. Fascinating because it delves deeper into how people think, how we form biases, and how we can be aware of them. This has not only taught me a lot about dealing with people but also about how I think about research.

Your career spans several decades, and even now during your emeritus, you remain very active. How have you seen the field of science and research change over the years?

I still believe that knowledge is progress. In the past, this seemed to be more valued. Today, fantastic discoveries are still being made, but society seems to take it for granted. Everyone finds it natural to have a new smartphone every year that can do even more than the previous edition. There seems to be a trivialization of the scientific process and scientific discoveries within society. This is also reflected in the strong rise of people who simply dismiss scientific arguments. Think of the sudden strong rise of the Flat Earth Society.

We will need science to find answers to societal problems. And that science will also change. We already see a strong rise of Artificial Intelligence that can handle Big Data. This has really started booming in recent years and will undoubtedly become even bigger in the future. We must embrace this.

.png)

What contribution to the scientific field do you hope your work will still have in 50 years?

I think plant biotechnology will be at the forefront of solving many problems in the future. Population growth is still ongoing, but the planet remains the same size. We need more arable land. I hope that such research can help, for example, in turning deserts into agricultural land. With the help of fungi, yeasts, soil bacteria, nematodes, etc., it should be possible to reclaim fertile soil here. Much knowledge is still needed to make this work, but I am hopeful.

Do you have advice for young researchers at the beginning of their careers?

Think for yourself, but above all, talk to people. Especially people outside of science! You can find inspiration and original perspectives everywhere. Know that you know so little and take pleasure in finding answers. Don't let it frustrate you. After all, pleasure stimulates the brain, so it only has benefits (laughs).

Closely related to this, I want to encourage everyone at the beginning of a scientific career - at the beginning of any career, actually - to be positive and remain optimistic. Don't be unhappy if you make a mistake. Admit your mistakes, learn from them, and move on with enthusiasm.

Finally, if you had not become a scientist, what would you have liked to be?

I have always been politically engaged. Because of that political interest, everyone thought I would go into politics. I have also always admired people who are very articulate and can convey their point in a clear manner. But ultimately, I am happy with my choice to become a scientist.

Thank you for this interview

Steve Bers

Want to be kept up-to-date on our biotechnological news and stories? Join our community and subscribe to our bi-monthly newsletter.

.jpg)