Bacteria as plant fertilizers: How soil microbes can help plants grow under drought

Farmers rely heavily on chemical fertilizers to boost crop yields, but this approach comes at a cost to soil quality, biodiversity, and plant fertility. Soil microbes may provide greener alternatives to help plants grow better under tough conditions like drought by triggering faster growth and earlier flowering. The intended result? Improved crop yields when water is scarce.

This story first appeared in Dutch on EOS blogs.

Plants and microbes are constantly interacting below the surface. These invisible relationships can be surprisingly powerful since some of them result in healthier plants. At the VIB-UGent center for Plant Systems Biology, scientists in the Sofie Goormachtig lab are investigating how these tiny helpers support the plants. “By tapping into these natural partnerships and understanding how they work at the molecular level, we can create sustainable, biological fertilizers that help crops thrive in dry environments,” says Sonia García Mendez, one of the researchers working on the project, who also participates in the Booster project that seeks to make maize drought-resistant with the help of bacteria.

Fight or flight – put to good use

Unlike animals, plants can’t run away from danger. They’re literally rooted in place and rely on a complex immune system to defend themselves. Traditionally, scientists thought plants had only one choice when facing threats: fight or die. But recent discoveries suggest plants might have a third option: to ‘flee’. In their own way, at least.

When under attack, plants can speed up their development, skipping the formation of extra leaves to focus on producing seeds. These seeds can then spread to safer ground. “Think of it as your house being on fire. You’re not going to start redecorating, right? You grab your family and go”, Sonia clarifies. “Plants do the same: they stop growing new leaves and focus on producing seeds as a way to 'escape' via their offspring.”

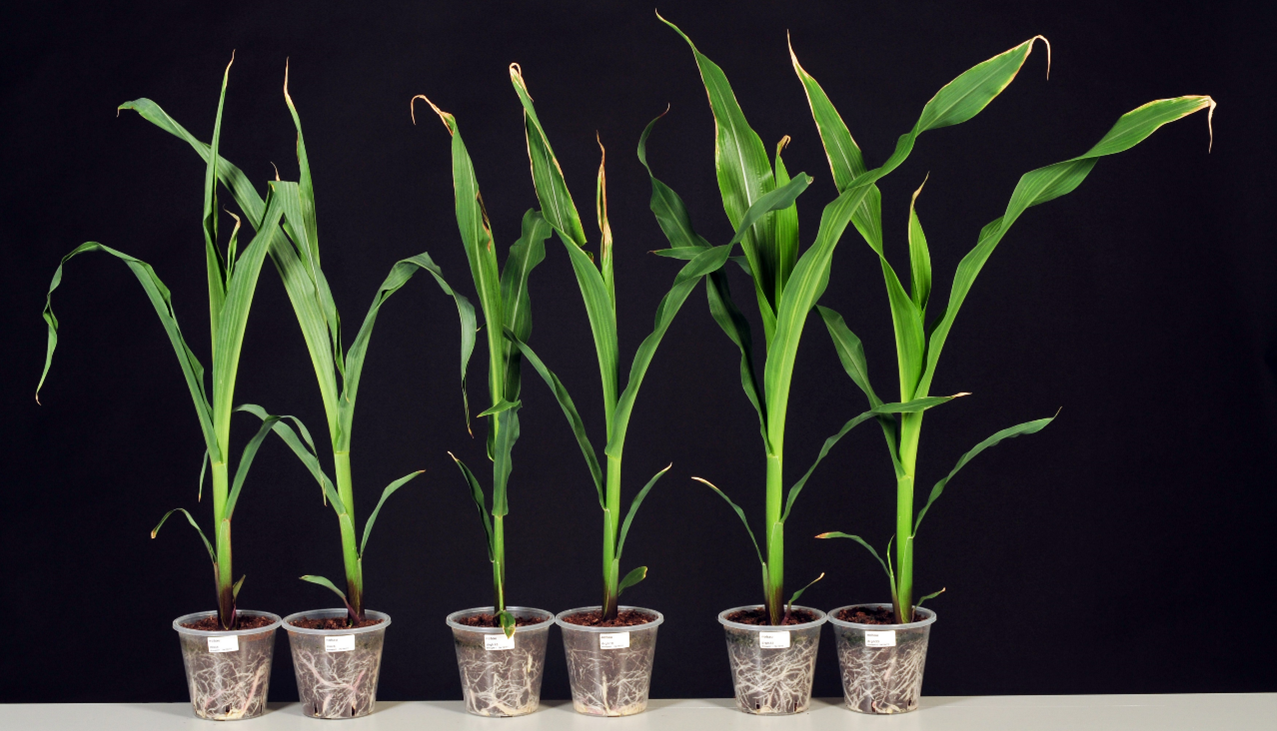

Interestingly, this escape response can be put to good use since friendly bacteria can also trigger it. In experiments with Arabidopsis thaliana (a type of cress used as a model plant), we found that specific genes linked to aging and flowering were activated upon treatment with certain soil bacteria. The treated plants bloomed earlier than untreated ones but without any loss in health or size. When the same microbes were applied to maize growing in dry soil, the results were striking: the treated plants were larger, greener, and more vital.

Super bacteria?

The bacteria behind these effects belong to a group called Streptomyces and can be found in nearly all soils. They’re also responsible for that ‘earthy’ smell you notice after a good rain shower thanks to a compound called geosmin. On top of their growth-promotion powers in plants, these microbes are famous for producing almost 60 percent of the antibiotics that we use in today’s medicine!

We suspect these Streptomyces may release a yet-undiscovered compound that prompts plants to reach seed production faster. “Since we do not see any harmful effects by the bacteria on the plants, this natural response could be harnessed to create biofertilizers that help crops survive drought and forces seed production. Whether this approach works for other crops like wheat or rice remains to be seen, but the outlook is promising”, Sofie Goormachtig concludes.

This type of research is helping us find greener solutions to combat climate change. Using soil microbes in biological fertilizer products, we can reduce the usage of harmful chemicals, protect the environment and improve human health. Next time you smell the scent of geosmin in the forest, think about the Streptomyces and their possibilities they provide for the future of agriculture. Sometimes the solution isn’t hard to find—it’s simply beneath our feet.