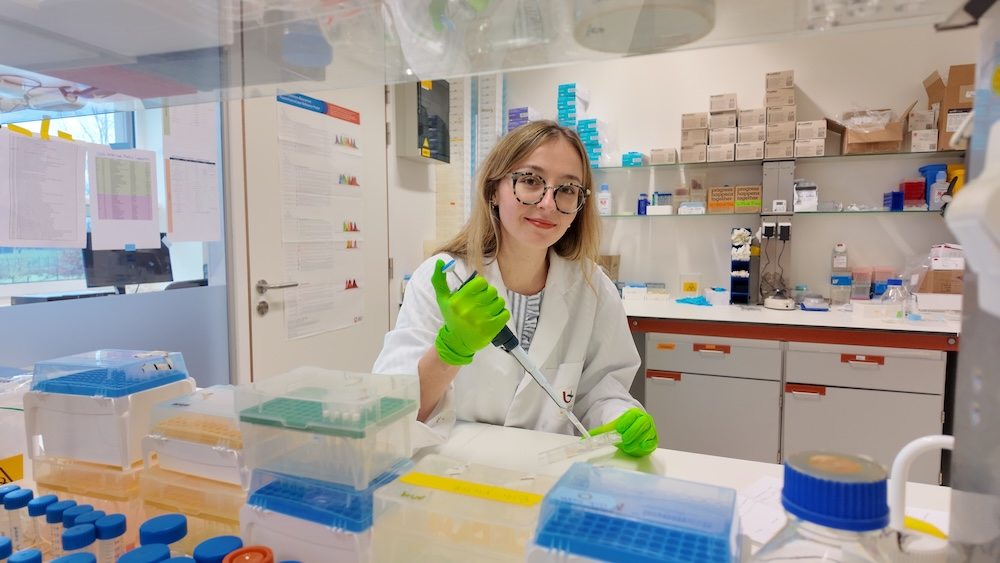

Dimitra Sokolova studies astrocytes, microglia and T cells from autism to Alzheimer’s disease

Dimitra Sokolova arrived at the VIB-UAntwerp Center for Molecular Neurology (CMN) in October 2024 with a clear motivation: keep building on what she knows best—glial biology in Alzheimer’s disease—while also stepping into new territory. Just over a year later, that ambition is paying off. As a postdoctoral researcher in the Pasciuto lab (Laboratory of Neuroimmunology), Dimitra has been recognised with two major accolades: an EMBO Postdoctoral Fellowship and the Queen Elisabeth Medical Foundation (QEMF) Young Researcher Award.

Dimitra spent most of her training at University College London (UCL). She began with a bachelor’s in biomedical sciences and, as her interests shifted, moved into a neuroscience track. “I became more and more interested in neuroscience,” she recalls. After working on pericytes in the lab of David Attwell during her bachelor’s degree, she first worked on microglia in the context of Alzheimer’s disease in the lab of Francis Edwards, during her master’s.

After graduating, Dimitra considered applying for a PhD position. When a position opened in the lab of Soyon Hong, who had recently joined UCL and the UK Dementia Research Institute, she decided to give it a shot, even though the deadline was close.

“I just sent my application on the day,” Dimitra says. It worked out, and, in hindsight, the timing mattered. “I was actually quite lucky that I started when I did,” she adds. “Because at that point COVID hit.”

On changing directions

Dimitra started her PhD in 2020. The project was co-funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and AstraZeneca, designed to combine academic and industry perspectives. In practice, the pandemic delayed parts of the industry collaboration, and the project’s scientific centre of gravity shifted. What began as a microglia-focused Alzheimer’s project gradually became more about astrocytes, and how their dysfunction contributes to synaptic vulnerability in Alzheimer’s.

Why the shift? Part of it was the project’s openness and Dimitra’s own interests. “Soyon’s expertise was microglia,” she explains, “but Oliver Freeman, my co-supervisor at AstraZeneca, was working with astrocytes.”

The biology also pulled her in, she says. “Originally, we started working on MFG-E8, an astrocyte-derived phagocytic tag. We found that it was highly expressed by a specific subset of astrocytes. When we reduced MFG-E8 levels, microglia engulfed fewer synapses, and synapse loss was reduced in different mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Over four and a half years, Dimitra developed deep expertise in how astrocyte dysfunction may contribute to synaptic vulnerability in Alzheimer’s disease. It’s a theme that has become increasingly important across neuroscience: the idea that brain disorders aren’t only “neuron problems,” but arise from disrupted interactions among many cell types—immune cells, astrocytes, and neurons all shaping each other over time.

A new lab, two projects, one shared idea

When Dimitra joined CMN, she was looking for a place where she could keep using her astrocyte experience, but also challenge herself by learning new tools and questions. She had already met Emanuela Pasciuto at conferences and was compelled by her work. Pasciuto’s lab examines how immune cells—particularly T cells—interact with the brain and influence neurological disease.

At CMN, Dimitra now works across two research tracks, both supported by the lab’s broader expertise, but each allowing her to lead and carve out a scientific identity.

One project, supported by the Queen Elisabeth Medical Foundation, is part of a research line exploring microglia-T cell interactions in Alzheimer’s disease. Microglia are resident immune cells of the brain; T cells are part of the adaptive immune system and are better known for their roles in infection and immunity in the body. In recent years, evidence has grown that T cells can also enter the brain in neurodegenerative disease and may influence inflammation and progression.

“My research focuses on how microglia and T cells communicate, how that communication shapes the behavior of both cell types, and how immune modulation might alter disease-relevant outcomes,” she explains. The research complements existing projects in the lab, including that of PhD student Amelia Zanchi. A longer-term, overarching goal is to connect the team's experimental findings to patient tissue, ensuring that what is observed in models maps onto human disease biology.

The second project, supported by her EMBO Postdoctoral Fellowship, brings Dimitra’s astrocyte expertise into a different field: autism. The Pasciuto lab works on autism models primarily through an immune lens, but Dimitra’s angle is complementary: what if astrocytes, and their interactions with synapses, contribute directly to circuit dysfunction in neurodevelopmental disorders?

“It’s a timely question,” she says. “Many autism risk genes have been studied mainly in neurons. Yet some are highly expressed in astrocytes, and their function in those cells is still poorly understood.” Dimitra’s project focuses on a specific genetic cause of autism and asks whether astrocyte changes alone can drive downstream neuronal effects.

“What makes this project especially meaningful in Antwerp is that the original disease-causing genetic change was first identified here at the University of Antwerp by Prof. Frank Kooy, a long-standing expert in neurogenetics and a collaborator on the project. That connection creates a direct bridge between clinical genetics and the lab’s mechanistic research: from identifying the mutation in patients, to asking what it actually does in the brain.”

The approach is multi-layered: imaging, molecular profiling, and functional readouts that range from cellular physiology to behavior, designed to trace a mechanistic path from gene to cell type to circuit.

What links both projects is a shared shift in perspective: away from a strictly neuron-centred view of disease, toward the idea that “non-neuronal” cells can be drivers, not just responders.

“Both projects look at how non-neuronal cells, be it astrocytes or microglia and T cells, contribute to the neuronal dysfunction that we see in these diseases.”

Growing as a researcher

Now, with two awards in hand and two projects taking shape, Dimitra is thinking about the next few years in realistic terms: the work ahead is substantial, and the publication timelines are long. Even her PhD work is still moving through the final stages. But the fellowships also create something rarer than funding: room to build a longer-term scientific direction.

“It’s tricky sometimes,” she admits. “But of course I am not doing everything alone.” One line of work is more advanced and was already underway in the lab when she arrived. It includes a PhD student, Amelia Zanchi, whom Dimitra supervises. The EMBO-funded project is newer, and Dimitra has support from a master’s student, Tuur Verreydt, who has been helping to establish parts of the workflow.

In practice, this means Dimitra is not only running experiments; she is also coordinating, mentoring, and setting priorities, developing the kind of leadership profile that fellowships are designed to nurture.

She sees both projects as spaces where she can lead: one by bringing her Alzheimer’s and glia background into an immune-focused lab environment, and the other by launching a more astrocyte-driven direction that is distinct within the lab’s broader research agenda.

“The EMBO and Queen Elizabeth Medical Foundation grant offer me the time, freedom, and momentum to push these questions forward.”